MEDIA INQUIRIES

Thank you for contacting the Eric and Wendy Schmidt Center. Your message has been received, and a staff member will get back to you shortly.

Oops! Something went wrong while submitting the form.

Uthsav Chitra joins the Johns Hopkins University as an assistant professor of computer science, faculty in the Data Science and AI Institute, and a member of the Center for Computational Biology.

Chitra received his PhD in computer science from Princeton University. Before joining Hopkins, he was a postdoctoral fellow at the Eric and Wendy Schmidt Center at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and a software engineer at Facebook.

I work in computational biology—specifically, developing algorithms for analyzing and interpreting large-scale biological data. Numerous technological breakthroughs over the past two decades—ranging from high-throughput DNA sequencing to single-cell/spatial genomics and CRISPR gene editing—have enabled scientists to measure diverse molecular modalities (DNA, RNA, proteins, etc.) across many biological systems (e.g., the brain or a tumor). However, existing machine learning (ML) frameworks often cannot be directly applied in this area because of the technical noise, sparsity, heterogeneity, and other unique aspects of biological data. As such, my research draws on tools from statistics, geometry, and graph theory to develop specialized algorithms for high-dimensional and multimodal biological data, with the broad goal of understanding biology at the molecular and cellular level.

I’m particularly excited by new computational problems in spatial biology. Recent “spatial transcriptomics” technologies measure both the gene expression and spatial location of individual cells, enabling us to understand how cells are organized and interact with one another inside our tissues. These datasets are also extremely sparse and high-dimensional, which creates unique mathematical and computational challenges. How do you model both the spatial geometry of cells and the high-dimensional geometry of gene expression measurements? How do you identify meaningful spatial patterns (e.g., continuous gradients) when there is such large data sparsity?

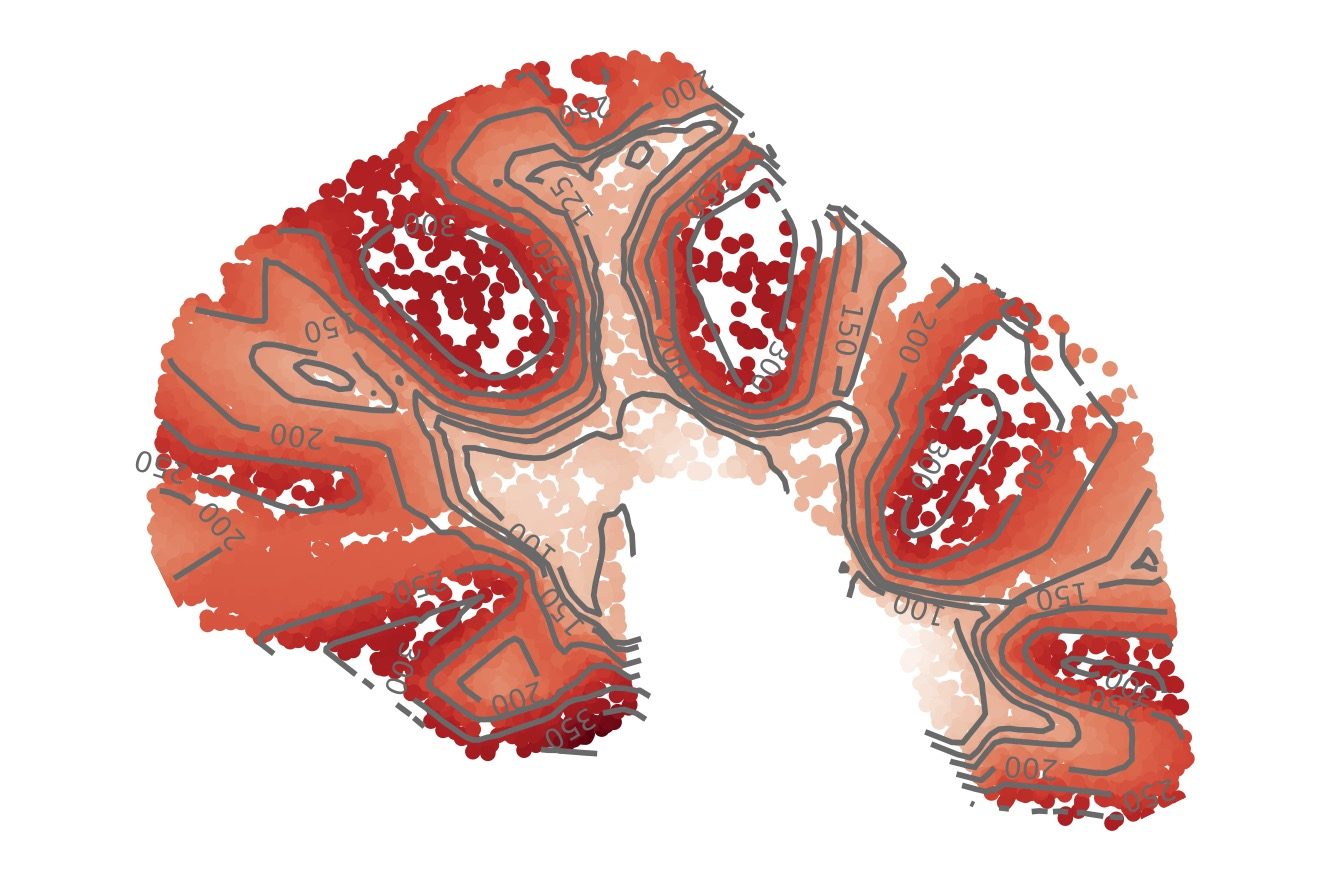

To address these challenges, we’ve developed new deep learning methods for learning “topographic maps” of tissues. Our topographic maps are analogous to elevation maps in geography, but instead of elevation, they describe a quantity called “isodepth” that reveals both the spatial organization of cell types and the spatial gradients of gene expression across a tissue, allowing us to visually “see” how tissues are organized. Mathematically, our topographic maps are based on a new model of spatial gradients in sparse data.

While I’m now in a computer science department, I’ve always loved the process of doing math: experimenting, devising, and mulling over my conjectures before writing up my arguments in a rigorous, airtight proof. But after two years of taking pure math classes in college, I realized that I ultimately wanted to do work with more real-world applications. By pure coincidence, I did a summer research internship with a former mathematician who moved into computational biology; I enjoyed the experience so much that I stayed in the field and did my PhD with him. I like working in computational biology because I get to develop mathematical frameworks and ML algorithms that address fundamental problems in biology, thus marrying my love of math with my desire to create a tangible impact with my work.

One especially exciting part of working in computational biology is how fast the field evolves. New biological technologies are constantly being developed, and each new technology brings new kinds of data and new biological questions that existing methods can’t quite answer. It’s fun being in a field where the problems aren’t fully defined yet and where developing novel mathematical ideas and ML algorithms directly impacts how we understand biology.

This semester, I’m teaching a graduate course on advanced topics in single-cell and spatial biology. In this class, students read and discuss research papers on computational methods and ML algorithms for single-cell and spatial genomics data, covering topics such as clustering, dimensionality reduction, optimal transport, and foundation models. In addition to teaching students how to read research papers, I also hope to teach them how to translate biological problems into clear and rigorously defined computational problems.

Johns Hopkins is an incredibly exciting place to work at the intersection of biology and AI/ML. The university is a powerhouse in biomedical research—its Schools of Medicine and Public Health are among the best in the world—and researchers here are constantly developing exciting new experimental technologies and generating rich biological datasets. Even in the few months that I’ve been here, conversations with experimental biologists have been a major source of motivation for my own research. At the same time, Hopkins has a growing and vibrant AI/ML community, with the department hiring many strong faculty through the Data Science and AI Institute. I’m very lucky that all of these exceptional researchers are my colleagues!

I’m also excited to be working in a department with such strong students. Hopkins students at all stages—undergraduate, master’s, and PhD—are exceptionally strong, curious, and motivated; I’m looking forward to mentoring and collaborating with them.

I enjoy rock climbing, specifically bouldering. Since moving to Baltimore, I’ve been climbing regularly at a nearby gym and exploring local outdoor bouldering spots in Maryland. The climbing community here is very welcoming!

This article was originally written by and for the Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering.